Interview featured in Sony’s “Social Issues and Technologies” special edition

- 2020.09.08

- 対談

An interview between Masatoshi Funabashi and Keiichiro Shimada was featured in Sony’s in-house magazine “Social Issues and Technology: On the Frontiers”. Reprinted here with permission.

- 1. Synecoculture™ began as a fundamental approach to social issues

- 2. Difference between domestic and overseas attitudes toward social issues, as seen from activities in Africa

- 3. The future shape of Japanese society, and a new role for science

- 4. Social issues that cannot be solved with approaches starting from current situations

- 5. Creating a culture and providing the technology to support it at Sony

- 6. It is necessary to have an approach that induces changes in global awareness and incorporates them

- 7. Similarities between the COVID-19 crisis and the nature of economic and environmental problems

- 8. Taking infectious diseases as a chance to understand nature and using that understanding as the foundation for human civilization

- 9. What needs to be done to realize long-term value globally

- 10. Creating a World Where People and Ecosystems Experience Kando with Sony’s Employees

Social Issues and Technology: On the Frontiers

“Biodiversity and Social Issues”

Interview Participants:

Masatoshi Funabashi (Researcher, Sony Computer Science Laboratories, Inc.)

Keiichiro Shimada (Executive Chief Engineer, Sony Corporation)

In the series “Social Issues and Technology: On the Frontiers,” we will be discussing the theme of contributing to solving social issues through internal technology. Much of the technology that Sony has worked on until now has been geared towards the content entertainment industries, such as Pictures, Music, and Games, but as society becomes more and more digital, those same technologies are actually becoming more closely related to solving social issues. For example, as we are conducting this interview remotely over video message as a measure due to the new coronavirus, that means the video, sound, and communication technologies used to make that possible can be considered part of the effort to solve social issues. This series of interviews attempts to answer the question of how Sony can solve social issues through our technologies.

This time we will be tackling the subject of “Biodiversity and Social Issues.”

Synecoculture™ began as a fundamental approach to social issues

Shimada:

Funabashi-san, thank you for taking the time to speak with me. For the people who don’t know, can you please talk about the nature of your work activities, as well as your thoughts on solving social issues?

Funabashi:

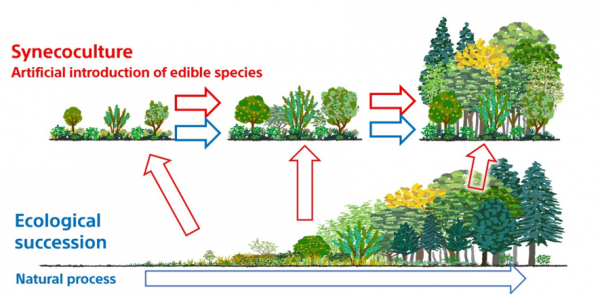

While people have different approaches in determining what constitutes a social issue, I believe that there are social issues that are difficult to solve by arbitrarily acting based on their own ideas of what is good, or just by following the conventional wisdom of modern society full of freedom, including economic freedom and freedom of thought. In sociology, this is called the “social dilemma.” Especially, environmental issues involve complex, underlying networks of casual relationships, and real progress cannot be made without a common goal, even if certain governments and organizations put in a lot of effort individually. This issue is particularly prevalent now in the 21st century, in which science, industry, and the global economy have all advanced to a certain point. We need to think out ways to solve social issues that incorporate these extensive causal networks of the society and natural ecosystems. I realized around ten years ago by process of elimination that if food production doesn’t eventually change, then it will be impossible to take a fundamental approach other than to simply treat the symptoms of the issue. Because of this, I am researching something called “Synecoculture™.”

Shimada:

I believe the global awareness of social issues has changed over the past ten years, with things such as the instatement of the SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals). Have you noticed this change in any way?

Funabashi:

I set the goals on social issues that were determined as necessary to solve by the year 2045, so I haven’t changed personally, but the reactions of those around me have been slowly changing. Rather than from the farmers, the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries, and the agriculture companies currently engaged in food production, I’m seeing these changes in the form of people in other industries not directly related to food production becoming more interested in this subject. Among those in the agricultural field, corporate sectors have shown the most interest.

Speaking of government, foreign government institutions and international organizations have started to get actively involved over the last five years. So I think there is a big difference between Japan and the rest of the world. Currently, we are receiving a lot of inquiries about Synecoculture from foreign government agencies, international groups, and NGOs, whereas our inquiries from within Japan are coming mostly from corporations and academic groups.

Difference between domestic and overseas attitudes toward social issues, as seen from activities in Africa

Shimada:

What do you think causes these differences in awareness between Japan and overseas?

Funabashi:

It depends on the country, so I can’t give a general answer, but there are places around the world that are starting to see the negative effects of biodiversity loss, environmental degradation, and climate change, and this is where the inquiries are coming from. Thus, Synecoculture is being undertaken by governments and international organizations that are concerned with taking countermeasures quickly. On the other hand, Japan isn’t currently in the midst of such a critical situation.

Shimada:

I understand you are actually visiting emerging and developing countries, but are there differences in the awareness of solving social issues between Japan, the US, and Europe?

Funabashi:

In developing countries, people are constantly concerned with things like how they are going to make the food they will eat tomorrow and the gradual deterioration of their environment that accompanies development, and there is a strong sense of crisis that this is becoming a huge problem. In Japan, nature has always been abundant, and the highly sophisticated society allows people to rely on others and not worry about having food to eat today, tomorrow, and even many years down the line. Because there is this environment in which people are able to focus only on their own work and the issues that affect them directly, there are few opportunities to thoroughly discuss the fundamentals of food production in a public space.

Furthermore, the actual solutions undertaken in the initiatives couldn’t be more different. For example, in developing countries, a solution called “decent work,” in which people can work safely without endangering their health or being economically exploited due to overwork, is urgently needed so that physical laborers can earn a proper income. However, as the social structure of making a living through a small amount of physical labor has already been lost in Japan, Europe, and the United States, applying the same solution to these developed nations would not produce an effective result.

Shimada:

I understand you are doing work in Burkina Faso in Africa. What fueled your decision to start work there?

Funabashi:

At first, I was running experiments with the Japanese ecosystem, and then I constructed a theory that connects the differing definitions of productivity in agriculture and ecology. This is described by the integrated theory of physiological and ecological optimization, on which I have published a paper [2]. Using this theory, I predicted that the benefits, power, productivity, and environment recovering effects of Synecoculture compared to traditional farming methods could be more thoroughly demonstrated in areas with extremely difficult environmental conditions and challenges such as desertification, rather than in an environment with favorably moderate climate and abundant precipitation, such as Japan. This is what led the decision to start experiments in the Sahel area of Sub-Saharan Africa as a representative example of these harsh environmental conditions, and we began experimenting in collaboration with local NGOs around the beginning of 2015.

Rather than relying solely on external frameworks of international support, we were able to have Synecoculture welcomed and proactively implemented by African NGOs that were closely connected to the local communities. Because of this, we exceeded our predictions in three years of experimenting, and it became necessary to upwardly revise the theory [1]. We also held five international conferences with the support of UNESCO and local government agencies. From these experiments where the climate, environment, and social structures vary greatly, I learned that social implementation is not possible without educational and technical support in line with a willingness to change from the locals, no matter how sophisticated the technology brought in by an outside group.

The future shape of Japanese society, and a new role for science

Shimada:

Based on these experiences, what kinds of options for change do you see in Japan’s future?

Funabashi:

Transitioning to a “sextiary sector” (a management system in which primary industries such as agriculture and fisheries are combined with secondary and tertiary industries such as food processing and distribution), which remains dependent on the current agricultural sector, is little more than symptomatic treatment for the disparity that resulted out of sophistication in the post-war industrial structure. In reality, the basic production principle remains the same as conventional farming while remaining reliant on external resources, and we cannot escape from the tradeoff between production stabilization and environmental destruction brought about by monoculture. Government-driven initiatives for smart societies, such as Society 5.0, have not been targeted at the ecosystem processes that form the foundation for sustainability, so it might be difficult to construct an infrastructure with true sustainability and scalability.

If we are to comprehensively consider Japan’s sustainability, in order to support the transition into a decentralized society, I think it is necessary to convert to a lifestyle that combines multiple jobs that are connected to urban areas and economic zones such as through remote work, while circulating the agriculture, forestry, and fishery industries based on basin units connected by the water cycle. Just as citizens in democracy prevent a dictatorship by spending the time to make informed political decisions such as through voting, in order for food production to achieve a healthy rate of self-sufficiency, people of all occupations will need to devote a portion of daily activities to efforts that will contribute to food production and the conservation of the ecosystem. For example, I believe that by requiring people from all industrial sectors to devote a portion of their working hours to activities that support citizen science related to biodiversity and food production, we can achieve long-term sustainability and a higher quality of life that will offset the short-term loss of productivity in individual sectors. If higher synergies are required, there is ample opportunity to generate positive value in the short and long term if the reproduction of natural capital by Synecoculture and the augmented ecosystems can be successfully combined with changes in social structure [3].

Environmental issues have not been fundamentally mitigated by the three-way separation of legislative, executive, and judicial systems described three centuries ago in Montesquieu’s treatise “The Spirit of the Law” that saved democracy from dictatorship. It is time to revise the fundamentals of the democratic society by fully addressing empowered aspects of the existing structure of modern society, such as the incorporation of science that has rapidly developed since the Industrial Revolution into the center of democratic decision-making as the “4th independent power [4].” If the judiciary is the guardian of the law, science should become the guardian of sustainability. The essential mechanism of the separation of powers of the government continues to this day largely unchanged since its inception. As there are only a few voting opportunities per year, and only one party or candidate is selected from a given list at a time, our involvement in democracy has stalled at the stage of essentially writing a few bits of information out in paper and pencil (※ Representation of a person’s name with word processing software generally requires more than several bytes of information, but in the case of a candidate list given in an election, for example, the information necessary to specify one from 32 candidates is equal to log32/log2 = 5 bits).

At the same time, modern AI can automatically process various expert judgments, and communication platforms exist in the world of online gaming such that numerous players can cooperate in complex strategies simultaneously, and a mathematical structure that can achieve total optimization for voting algorithms has been revealed. By combining all of these technologies, it would be possible to establish science as the “4th power” most familiar to citizens with unprecedented scale and usability in order to enhance sustainability by connecting real diversity and democratic decision making in an extremely effective way. Currently, international treaties and governmental actions concerning sustainability are only being discussed by political representatives and certain experts, and we have reached a situation in which monitoring and control cannot effectively keep up. Because of this, we need to create a system in which global citizens can contribute to the sustainability of human society from the various places where they live, while still maintaining a connection to the whole. In order for comprehensive goals like the SDGs to be accomplished, there needs to be a fundamental shift in the organization of society as well.

Social issues that cannot be solved with approaches starting from current situations

Shimada:

Speaking of the differences between Japan and other countries, in Japan it is often the case that individual farmers work together with agricultural cooperatives, but overseas I think that agriculture is being commercialized or that even individual farmers are working on a very large scale. Are there any positives or downsides to the work you are doing relating to these differences?

Funabashi:

It’s not that actually that relevant. If you work to capitalize on agriculture, the economic incentive to up-scale operations through monoculture will work in the short term. However, the problem is that this is not sustainable in the long term. Therefore, whether or not the introduction of Synecoculture is easy or difficult due to organizational or economic reasons is only a phenomenon of the present time. From now on, from the viewpoint of virus epidemics or environmental protection for example, it will become necessary to break down a large-scale monoculture from medium to small scale and carry out activities to promote biodiversity, such as through collaborating with other industries. Predicting such a future, we have been studying the basic state and production principles of the new sectors that we need to create. Hence, the introduction’s ease or difficulty is not a high-priority issue to think about at the present moment.

Under current status of science and business, whether the source of funding comes from economic activity or from government subsidies, policies are still dictated by the will of large agricultural firms, and as long as we continue to think of money flow in this way, the promotion of biodiversity with small-scale farmers as important actors will not go forward. On a global scale, charitable work and perfunctory international support initiatives are being funded and then ending within three years. However, when the amount of food produced by family-owned smallholders is added up, it equals a majority of all the food currently being consumed on the planet, and at the same time, this has become the cause of environmental destruction to the extent that cannot simply be solved by making gradual and incremental improvements starting from conventional practices. As I mentioned before, global food production is a representative example of a social issue that cannot be solved through separate individuals’ actions and improvements. Therefore, as soon as it is obvious that if certain actions aren’t taken by 2045, then the current global population, health, and ecosystem diversity cannot be maintained, then qualitatively drastic measures must be taken in that direction. We have taken the stance of thinking about the necessary knowledge, technology, and business methods for when that time comes.

Creating a culture and providing the technology to support it at Sony

Shimada:

At Sony, we have been discussing business activities not only for the purpose of generating profit, but for contributing to solving social issues as well. How do you think the technology of Sony engineers can contribute to solving SDGs and social issues? Also, is there anything that could be of use for Synecoculture?

Funabashi:

I don’t think there are many social issues that can be solved with technology as the main contributing factor. Instead, I think formulating the social organization of humans, the use of nature, and culture, and then introducing technology as a way to support that culture, is perhaps the right way to go about it.

To give an example using Sony, we have this great invention of the Walkman®, which didn’t come about through thinking about what to do with technology, but rather as a form of lifestyle proposal. There was an idea for a lifestyle in which music is enjoyed not just at a concert, theater, or at one’s home, but rather while moving around a city or even in nature. In order to realize that concept using the currently available technology at the time, the Walkman® was born. I think that the tradition of proposing a new culture and then supporting it with technology is actually a strength that Sony has over other companies. I think it will be necessary for us to carry on that DNA to take on new situations. Therefore, I don’t think it’s necessarily a good stance to say, “Because we have these great technologies we can solve social issues.” We should rather be thinking of how culture and society need to be as a whole in order to solve these issues, and then from that qualitative standpoint, we can finally start to think about how to utilize Sony’s technology.

As a typical example of the current situation, while AI is being used for foreign exchange trading, trading at super-high speeds that surpass human ability through AI actually leads to instability for a majority of exchange translations, so in the end, it is becoming clear that the most robust traditional investment strategies offer the least risk.

This is a typical situation of vulnerability due to a reliance on AI, causing the loss of resilience and robustness. I call this the risk of being “AI-dependent,” and what we need instead is to create a situation I call “AI-supported.” It is the complementary use of AI to support the creation of a more efficient organization for society and culture that allows humans to become smarter, respects diversity, and has a high level of social-ecological integrity. The top priority is to use technology as a tool under a bigger context of raising overall standards for the ecosystems and environments in which humanity is involved.

Shimada:

I wanted something like a Walkman for many years before the product was actually introduced into the market. I wanted to be able to listen to music I personally enjoyed while commuting to places like school, but the technology was not there yet. There were many issues to overcome, such as low power consumption, miniaturization, high-density mounting, and sound quality for headphones, and I was very happy when technology finally overcame those hurdles in 1979. So, for me, I do get the sense that the demand for a potential lifestyle came first, and then the technology was developed later.

Funabashi:

I think it’s a very important example. When it comes to recent startups and new business models, the way of thinking of, “We have this technology so this kind of culture is possible,” has become very dominant. Now, this kind of thing may lead to certain affluent people improving their quality of life a little bit more, or it may inspire some people to raise their creativity. But as I mentioned earlier, as the global population increases, environmental issues such as biodiversity will not be solved without the improvement of the culture for many smallholders, who are the world majority in food-production areas. I think it is necessary to raise the cultural standard for humanity as a whole, not just the gadgets of the wealthy people in some urban areas, and I think we need to bring forth fundamental socio-technical shifts utilizing more profoundly a Walkman-like idea.

As a matter of fact, old Walkman and radio cassette models that are no longer even sold in Japan are still being listened to in the African countryside. Little things to improve their lifestyle are scattered all around their unpaved streets and inside tiny stalls. This is a symbolic example of what needs to be done to change these smallholders’ lifestyles who are not being reached sufficiently by science, business, or government. Among the companies that can think deeply about the culture and the technologies that support it, I think Sony is in the top class in terms of both quality and quantity.

It is necessary to have an approach that induces changes in global awareness and incorporates them

Shimada:

Both government and the business world see solving social issues as an integral part of business, but how do you personally view the relationship between business and social issues?

Funabashi:

I think there are various different perspectives regarding commercialization. For example, even if fancy people are simply doing what they like as a hobby, there is a tendency to be treated as a business because much money is flying around. On the contrary, no matter how much you can say something is essential for sustainability, if people and funds don’t follow, it is nothing more than just fancy talk. Moreover, the value of so-called natural capital, such as long-term profitability, sustainability, health benefits, and the regeneration of biodiversity, are not incorporated into real-time economic activity. Sometimes, they have the difficulty of only being possible dozens of years too late. I think the challenge is to see how much we can recognize these things and turn them into common values. In a capitalistic society in which only profitable businesses are being promoted under the current business model, biodiversity will sooner or later collapse globally, water and air will no longer be available for free, and an explosion in value that money cannot buy will occur. The catastrophes that will cause these conflicts can already be seen today. So in reality, we are currently in the same place we have been up until this point. We are too late in making decisions whether to monetize risks that have been predicted but not yet actualized, and incorporate them into a current business protocol. Because the nature of the environmental risk is outside the scope of market rationality, and there is always the chance that what actually occurs may be different.

Similarities between the COVID-19 crisis and the nature of economic and environmental problems

Funabashi:

One important fact is that some trillion yen of economic loss has occurred just in Japan alone due to the novel coronavirus, with a global estimate of several hundred trillion yen. This is something that couldn’t have been predicted before 2020, and such a sudden, extreme economic loss is indicative of the very nature of environmental issues. Regarding whether proactive measures can be taken without leading to a situation such as COVID-19, possible options remain qualitative and generalized. Even if we know the general direction, be that promoting biodiversity while keeping a clear distinction between wildlife and human habitat, maintaining healthy topsoil, or shifting toward a decentralized society to end workstyles that push people to their physical limits as well as high-density housing and heavy commuting habits, the question is whether we can take countermeasures worth several tens of trillion yen starting this year in order to avoid the risk of a sudden economic collapse 20 years from now. And to justify that, the question is whether we can create a common context to work along that goes beyond the profitability of individual companies and is carried out at the level of local communities, countries, or even all of Asia or the whole world. In the way of business-as-usual scenario, with individual companies all pursuing their own profits, we cannot access the benefits of the dynamics originally possessed by nature, and we cannot take measures against the risk of a large-scale crisis like COVID-19.

I think the first step is a battle of recognition regarding how we can apply our economic activities or scale-up the target areas for events beyond the simple transaction of money. After that recognition is shared to a certain extent, there is a judgment to be made, whether each business’s pros and cons are contributing to an overall cause. Moreover, in order to contribute to the utmost improvement across the board, tailoring from large goals to small goals needs to be done, so that individual businesses in each scale can make profits, pay salaries, and support economic activities to buy and sell necessary goods.

That is not happening at the moment. For example, while there is a certain degree of context sharing within the Sony Group, it’s not the case at all that Sony and other companies, such as those that are part of the Keidanren (Japan Business Federation), are sharing a common goal of avoiding the risk from the loss of the Japanese environment or natural capital and thus taking those ideas back to review each individual business. I think that the prevailing practice in management is basically to maintain your own company while cooperating and competing with other corporations under an opportunistic strategy. An extremely difficult refiguring of civilization will be necessary, in which businesses of all sizes and the government(s) of Japan, Asia, the United Nations, or the Convention on Biological Diversity all properly share a unified direction. We need to create a strong platform for profit sharing to economic agents of various sizes while accepting the multiple advantages and disadvantages therein through securing larger common benefits.

Taking infectious diseases as a chance to understand nature and using that understanding as the foundation for human civilization

Shimada:

I was under the impression that a pandemic of an infectious disease like we are experiencing now was inevitable to a certain extent, or that we had created a situation that made it easy to occur. I feel that now we are under pressure to create a sort of cultural reset that you just mentioned.

Funabashi:

Infectious diseases also have their purpose, and in a world without them, it would actually be difficult to maintain a healthy ecosystem. The dynamics of ecosystems are extremely complex and full of intricate cooperative and competitive relationships between animals, plants, microorganisms, pathogens, etc. Infectious diseases play a role in creating balance and diversity that allows the entire ecosystem to survive large geological and astronomical events like volcanic or solar activity changes. Even if they present problems or inconvenience for humanity, infectious diseases have a solid and necessary role for ecosystems, much of which is not yet fully understood by human science. Rather than fear it, we should take this a chance to understand the living world in a wider context and then apply it to create a new civilization with a more synergistic relationship with nature. That will be the next evolution of humankind.

What needs to be done to realize long-term value globally

Shimada:

As you mentioned earlier, we have begun to see some innovations on the business side, such as the emergence of an investment strategy that considers the contribution to solving social issues as a form of long-term value creation, such as through ESG investment. Also, in relation to Sony, what do you think will be necessary for an approach to conduct sensing of the natural environment through technology?

Funabashi:

Since sensing is also a technology after all, it is impossible for a machine to sense something that humans cannot recognize. Of course, I understand the expectation that machines will be able to see things that humans cannot see, as they have multispectral cameras, for instance, which can detect wavelengths undetectable by the human eye. However, it was humans who were in the first place to think that this kind of thing can be understood by measuring with a technology called a multispectral camera. In other words, technology is of no use if there is no idea or awareness of the problem initially from the human side.

For example, regarding the current strict suggestion for people to stay home due to the new coronavirus, because we can’t visualize the bactericidal action of sunlight, we have a tendency to start making extremely generalized and unilateral statements. Of course, there is epidemiological evidence that speaking and gathering in close proximity to other people can cause the infection to spread, but it is human beings who have applied that idea unilaterally to places where the elements of the ecosystem are completely different, such as public parks and beaches, where there are ultraviolet rays, direct sunlight, wind, and healthy topsoil. No matter how much a machine understands that the infection rate is high in areas with the “three Cs (closed spaces, crowded places, and close-contact settings),” the imagination to apply it to other environments might be missing on the human side. This means that there is always a human element above that machine that is issuing commands and ideas.

Let us take ESG investment as another form of technology. At first glance, it sounds like it is properly targeting things that are not generally noticed when companies only focus on profits. Still, there are people working behind, who set the true contents of ESG and their long-term goals. We have to ask, to which extent are these people looking at the ESGs? Furthermore, if the only people promoting the ESGs were, for example, the heads of companies, there would be almost no way to actualize them. Considering that the impact of the ESGs goes beyond the stakeholders of any single business, we also have to think about how they will affect other sectors through the environment, as well as what the response on an ecosystem level will be. We first need to expand the power of imagination and create an all-encompassing context that includes everyday experience and science and divest a huge amount of effort into creating a common framework, such as for investment, for the benefit of everyone involved. Only then can we come to understand the addition of the ESGs and technology to what is shared among the community, and there will be no confusion of goals.

The same process also applies to the earlier mentioned example: Incorporating science as the “4th independent power” in a democratic society (in addition to legislative, executive, and judicial), which will become necessary as a way to monitor sustainability, will also demand prior revolution of the way we consider the institution of society itself. Only then, the next-generation Internet technology, for example, can be effectively used as infrastructure for that purpose.

Using climate change as an example, the goal of net-zero carbon footprint by 2050 will become an important CSR goal for sustainable corporate activities. Though, even if the apparent net emissions become zero, there are actually still various areas where it falls short. For example, even if you set the goal of achieving a zero environmental footprint by the year 2050, the 1.5℃ temperature increase scenario predicted by the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) will still occur if there isn’t a proper achievement of mid-term target by the year 2030. And even if apparent carbon emissions are reduced to zero, whether there is actually zero-carbon being emitted is an entirely different matter. Essentially, if you invest in afforestation then you can buy the right to emit carbon dioxide, but we do not yet have sufficient technology to monitor whether the forestry that was invested in is adequately absorbing the expected amount.

There needs to be monitoring to make sure that the carbon is being absorbed properly, and if it is not, the firms should follow up by investing more in afforestation or taking other methods. Even when limiting the conversation just to CO2, basic balance and its feasibility have to be thoroughly thought out first. And even if global warming could be prevented, for example, through continuing to do invest in forestry monoculture, this would result in the loss of indigenous biodiversity and a decline in ecosystem functions and services. So there is a possibility that humanity would prevent global warming but still end up in a situation with dwindling natural resources. As such, just by connecting current knowledge you can conclude that unless we offset not only carbon but also biodiversity as well, the world originally envisioned by the CSR goal will not be possible.

Accordingly, whether it is the ESGs or CSR, it is vital to thoroughly check all the details to make sure these initiatives are truly on track to achieve their goals by the necessary deadlines of 2045 or 2050. It requires a huge undertaking of figuring out how to incorporate technology into the overall context of social-ecological values.

Creating a World Where People and Ecosystems Experience Kando with Sony’s Employees

Shimada:

I think that one of the underlying themes when discussing social issues is how we approach nature as humans. Could you tell us what we should be careful about? Finally, do you have a message for Sony employees?

Funabashi:

There are only two types of interaction between humans and nature. That is, when humans interact with nature, biodiversity either decreases or increases. Among human history, the majority of our activities has led to a decrease in biodiversity. Therefore, if we are going in the direction of increasing natural biodiversity due to human beings’ existence, we will be able to maintain the ecosystem even if the human population increases, but in the opposite case, both humanity and nature will collapse together. I think it is absolutely vital that all of our interactions with and uses of nature in the future lead to an increase in biodiversity.

I believe that Sony is one of the few companies that can accomplish the things I have spoken about today, even now. Among the many great companies out there, Sony has a diverse business portfolio, experience, and a long timescale of creating a culture and supporting it with technology. As I mentioned, until now the promotion of most business activities has led to the destruction of natural biodiversity. Still, I believe that if Sony’s strengths are brought together, the more Sony’s economic activities develop into the direction that is healthy for the environment, the more biodiversity there will be on the planet. Perhaps this would be the first large company ever in human history to enact such corporate activities.

Ultimately, the world with Sony should nurture more biodiversity than a world without Sony. Then, the ecosystem functions will be enhanced, and natural resources such as water, air, and food, which are the fuel for our daily lives, will be developed in conjunction with the social capital that Sony handles. As a result, human happiness will also increase, as well as happiness in the sense that all creatures in the ecosystem can fulfill their roles in the rich natural environment. To put a world with such a Sony into other words, I believe it would amount to creating the biggest Kando for all living things on this planet. Sony can contribute to the emotion not just of humans but of actual ecosystems, if the emotion is made out of things that are spontaneously driven for all life. I would like to work together with everyone at Sony to work on those kinds of activities.

Shimada:

Thank you for this wonderful talk today.

[1] Funabashi M. “Human augmentation of ecosystems: objectives for food production and science by 2045” npj Science of Food volume 2, Article number: 16 (2018)

[2] Funabashi M. “Synecological farming: Theoretical foundation on biodiversity responses of plant communities” Plant Biotechnology, special issue plants environmental responses, 16.0219a

[3] Funabashi M. “Manifesto of Meta-Metabolism.” (舩橋真俊『メタ・メタボリズム 宣言』 南條史生 アカデミーヒルズ 編 森美術館 企画協力 『人は明日どう生きるのか――未来像の更新』NTT出版 発行 (2020) pp. 50-72)

[4] Ohta K. and Funabashi M. “Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) —Synecoculture—” in New Breeze, the Quaterly of the ITU Association of Japan (No. 2 Vol. 31 April 2019 Spring)

-

前の記事

「整える」こと 2020.08.18

-

次の記事

瀬戸内訪問: 直島・豊島・犬島・小豆島 2020.09.25